Sport, language and art in Shatila: voices beyond borders

Written by Clara Punzi

January 2025

January 2025

Workcamp

As I left Shatila on my way back to Italy, I could hardly foresee that, in nothing more than a couple of weeks, this fragile yet vibrant community would have soon find itself at the heart of renovated violence. Although there were signs of impending conflict, such as Israeli army overflights, sonic booms and assaults on Hezbollah around the country, life in the camp carried on with unwavering determination and perseverance for the inhabitants of Shatila.

Excitement filled the air, particularly within the Palestinian community of Coach Majdi. The indoor gym of the Shatila Community Sport Center, which we helped renovating alongside the camp workers, stood ready to welcome new basketball and boxing courses. The young girls and boys were preparing for the upcoming school year, some with enthusiasm, others with a hint of unfailing anxiety and reluctance. A new medical centre, led by a close friend of Majdi, was set to open soon right in front of the gym, offering free medical visits for the families of Shatila. Plans for new academic journeys and family futures were set forth by the youngest, intertwined with the aspiration of crafting a life of dignity, possibly far away. Yet, just a few days after I left and almost tragically coinciding with the anniversary of the Sabra and Shatila massacre (happened in 1982), these threads of daily life were shattered by the Israeli invasion of Lebanon, marked by relentless bombardment of the Beirut suburbs surrounding Shatila. Once again, the lives of the Palestinians, Syrians and Lebanese in Shatila were being put to the test in an unbearable and unwarranted manner.

As I reflected on what actions could be taken to stand with them upon my return home, memories of our time together flooded my mind, reminding me of the motivations that initially led me to embark on this journey. As I remembered, at first I struggled with my role in the workcamp, unsure of how I could contribute meaningfully and respectfully to the community. What were the expectations of the local partner and, above all, of the girls and boys with whom I would have spent my time in Shatila? The training sessions organized by SCI before departure offered a precious space to share these uncertainties and explore them collectively. Discussing my concerns with other volunteers and the trainers helped me realize not only that there are no universal answers to these questions, as each context is unique; but also that, probably, it is the act itself of holding onto these questions, that is, staying aware of them and feeding them with the lived realities of Shatila, that could make the experience of the workcamp meaningful for both the local community and myself.

Indeed, upon my arrival, it soon became clear that the most valuable approach was to immerse myself in its life, grasp its nuances from the voices and scenes all around and allow the local people to introduce me into their community. Residents of any age welcomed me with open arms, eager to share their stories, introducing me to their families and exchanging cultures. Their warmth and hospitality fostered a sense of connection, protection and safety, making me feel embraced by their community. From the very first day, the children’s excitement was palpable as they gathered to draw and play with us, regardless of our different origins and languages. Despite the stark differences in our circumstances, our shared humanity brought us together.

Soon enough, I found myself totally absorbed by the life in Shatila. With the precious support of Coach Majdi and of his entire family, I quickly started to feel and experience the daily life of the camp. At the same time, Coach Majdi encouraged me to get involved in the activities at his centre.

While he primarily provides sport lessons for young girls and boys, the Shatila Community Sport Center enriches the community by also offering language and art classes led by local teachers.

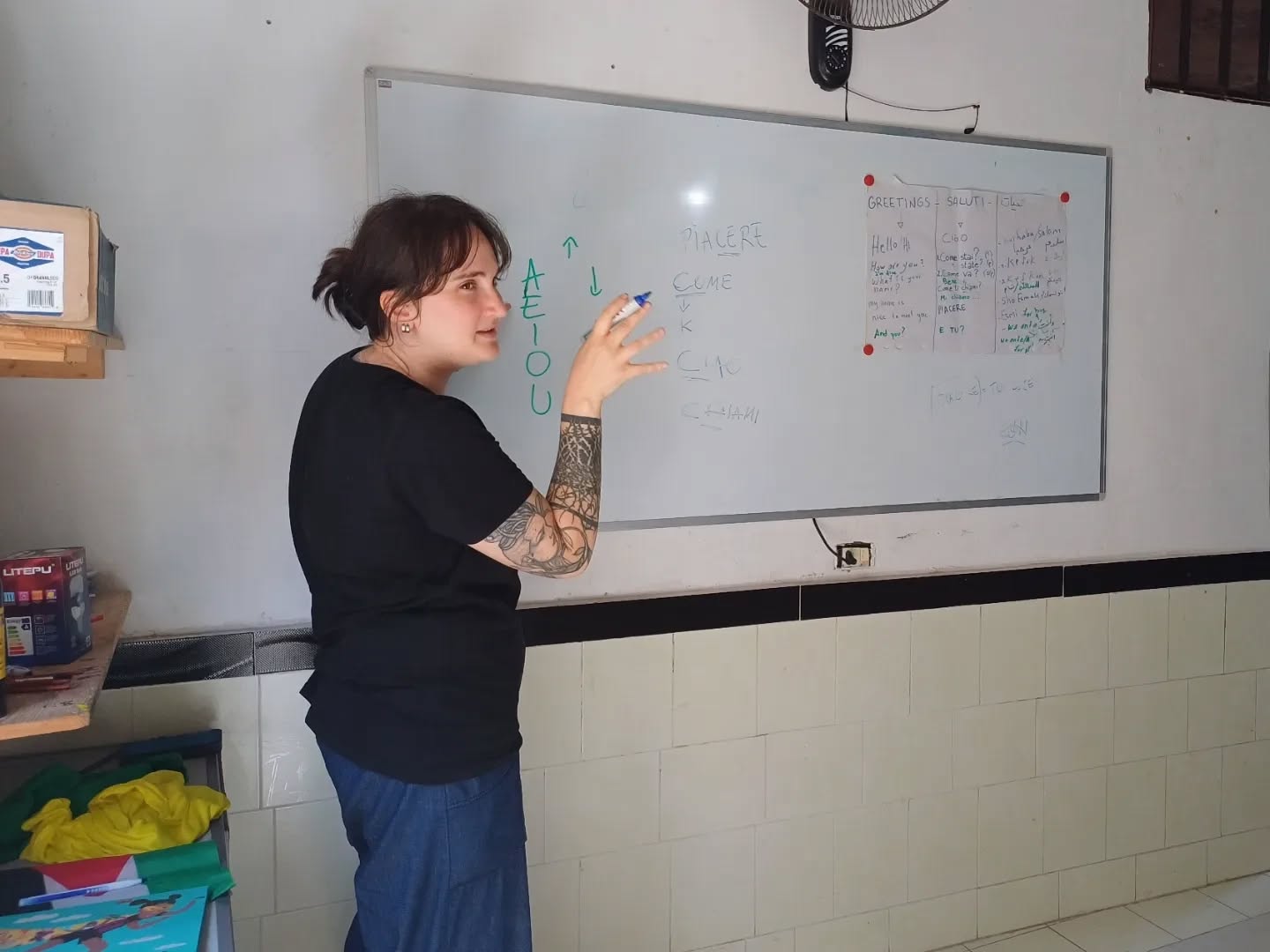

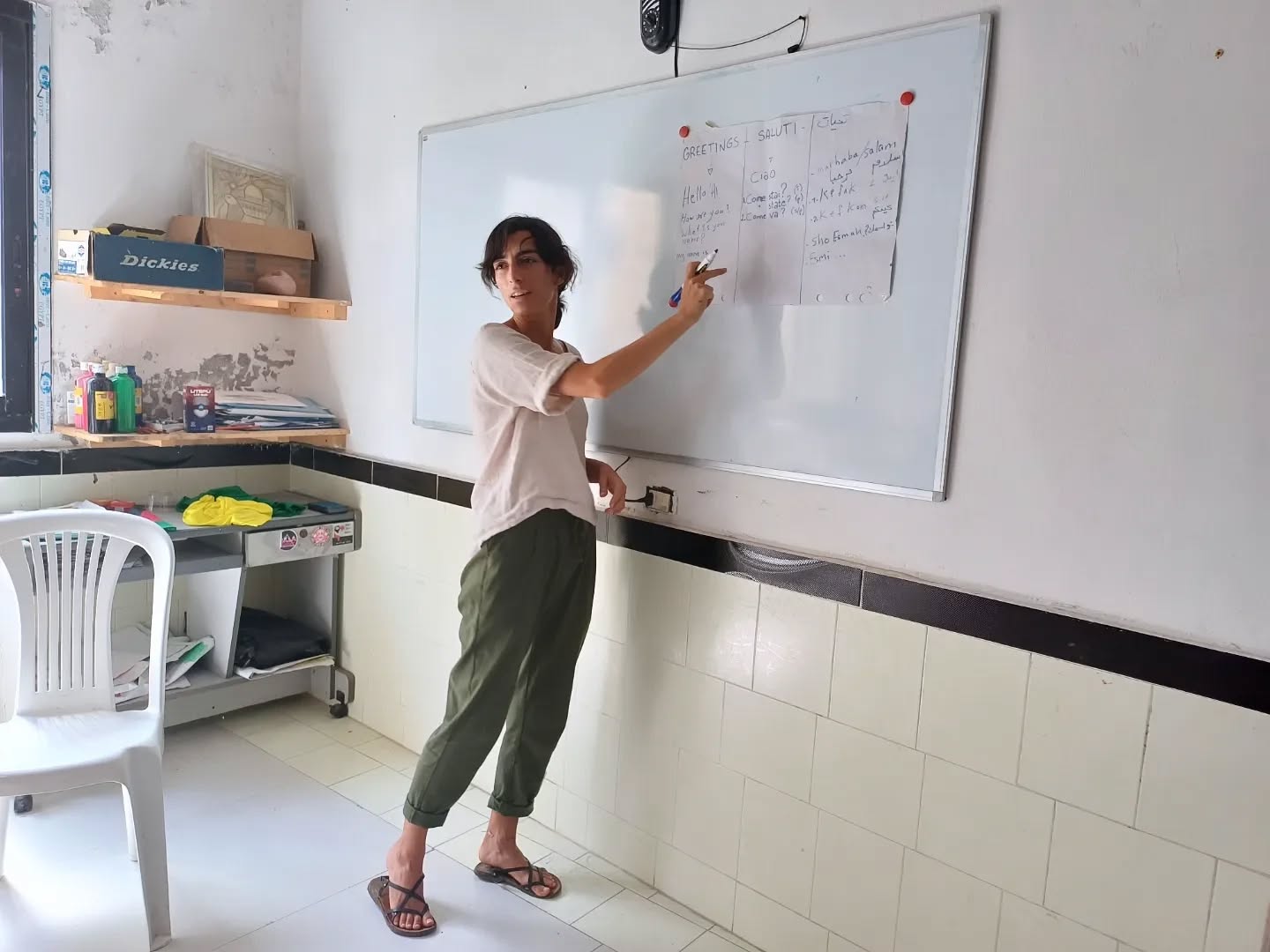

Indeed, together with them, we lunched an Italian-Arabic-English language exchange that, however, quickly became focused on Italian due to the enthusiastic interest shown by all participants. The dedication of the young girls and boys was stunning. For some, it was clear that learning Italian was more than a summer hobby; in the harsh condition they are forced to grow up, being able to speak Italian could be easily imagined as a window to a world beyond the camp’s borders. In those moments, language became for them a tool of empowerment, an imaginative leap into a life unbounded by oppression.

Our work also extended to assisting with art and sports programs at the Shatila Community Sport Center. During one drawing class, we created together an image of Handala, a symbol of Palestinian identity and defiance, walking alongside a basketball team of young girls. This image encapsulated the spirit of the mission that Coach Majdi has for the centre he leads: the use of sport and creativity as tools for personal and social growth, self-determination, freedom, justice and equality. The basketball program guided by Coach Majdi, in particular, stood out and has achieved significant results already. The program offers the girls not just physical training, but also teaches them the values of teamwork and gives them the opportunity to go outside the refugee camp to train and compete in matches against other local teams. In the past few years, some of the girls also had the opportunity to travel abroad and meet international basketball teams. Many of the girls I met in Shatila have a passion for basketball, yet being part of the team presents its challenges, stemming not just from the precarious situation of the refugee camp and the ongoing conflict. Fortunately, their coach is always there to help: he emphasizes the importance of mutual respect and dedication, guiding them through every training session to balance their commitments in both school and sports. In his view, these are the key elements for building a better future for them, grounded in solidarity and freed from injustice and oppression.

Among the many experiences and lessons I brought back from Shatila, one that stands out strongly is the obvious yet striking realization that years of conflict and oppression deprive people not only of resources but most crucially of their fundamental rights and dignity. While this is often acknowledged in discourse, witnessing it first-hand imparted a tangible weight to these realities. While material resources are often essential for achieving one’s ambitions, the pursuit of wealth devoid of prior liberation appears to be ultimately vain. For instance, what value does education and academic success hold when your citizenship status bars you from employment opportunities or mobility, as it happens to thousands of Palestinians in Lebanon? The rights to exist, to belong, and to self-determination must be first recognized to start dismantling the chains of systemic oppression.

This call, woven into the voices, faces, and images I encountered, echoes with strength in Shatila. It struck me as a reminder that every collective struggle is imbued with the unique, colourful humanity of those who fight for it. And that, conversely, an individual struggle that is a struggle for many can be seen in a new transformative light when embraced collectively.

Back in Italy, I wrestled with how to let the experience of the workcamp expand beyond the borders of Shatila and of my intimacy, striving on if and how to share it with my community. The subsequent Israeli bombings of Beirut’s southern suburbs, precisely where the refugee camps of Sabra and Shatila are located, made my hesitation rather moot. The urgency of the situation demanded action. Sharing the stories of the many new friends I encountered in Shatila became a way to amplify their voices and spark conversations about the rights of Palestinians, the legacy of statelessness and contradictions of refugee status, as well as the everlasting systemic oppression perpetuated by the Israeli regime through both persistent psychological terror and growing military actions that have abruptly escalated into a cruel genocide. These discussions evolved into deeper reflections on our roles and responsibilities as global citizens; on how we, too, are implicated due to our colonial past and the current complicity of our countries; and how we can act in solidarity, motivated by an understanding of shared struggles while fully respecting the needs of those directly affected by the conflict.

The news of the Shatila Youth Center reopening its doors after weeks of conflict filled me with hope. Despite the devastation and uncertainty, the centre resumed its activities, offering the young girls and boys still living in the camp a safe place where they could reclaim fragments of tranquillity and enjoyment in their lives. This workcamp opened my eyes to the fact that the refugee camp of Shatila, especially its Palestinian community, is a testament to the enduring spirit of people who refuse to be erased. It is a place where hope exists despite unimaginable challenges, where even the smallest acts of resistance, such as learning a new language, picking up sport classes or creating art, carry profound political weight. The camp’s resilience and humanity demand not only our attention but also our commitment to advocating for justice and an end to the conditions that sustain and perpetuate this seemingly never-ending spiral of oppression.

You can still join!

Want to have your own volunteer experience for peace?